‘PAYING THE RENT’

Jessie Lewis

on

12 May 2023

'PAYING THE RENT'

A SMALL PERCENT

Breathe for Aboriginal Housing Victoria

LOCATION

VIC

Reservoir

Umarkoo Wayi – Gangu Gulin Country

We acknowledge the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation, the Traditional Custodians of the land upon which Umarkoo Wayi – Ganbu Guljin stands. We recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and culture.

Paying the rent is a requirement of every nightingale housing project. Nightingale housing have instigated a simple pay-the-rent system, it is only a small percentage of the owners corporation fees per year (we know it’s not enough, but it sends a clear message).

This revenue is donated to First Nations organisations under the direction of First Nations Elders to the Nightingale Housing Board.

The hope is that others choose to do this in the future. and that the money goes to, in some small way, start tackling some of the issues of inequality faced by First Nations people.

Explore Further

OPENNESS TO WATER’S UNRULY HABITS

Ben Cottam

on

12 May 2023

OPENNESS TO WATER'S UNRULY HABITS

INSPIRING PROCESSES OF MEMORY, REPAIR AND STEWARDSHIP

baanytaageek: Great Swamp Regenerative Collective

LOCATION

VIC

Tae Rak (Lake Condah)

Gunditjmara Country

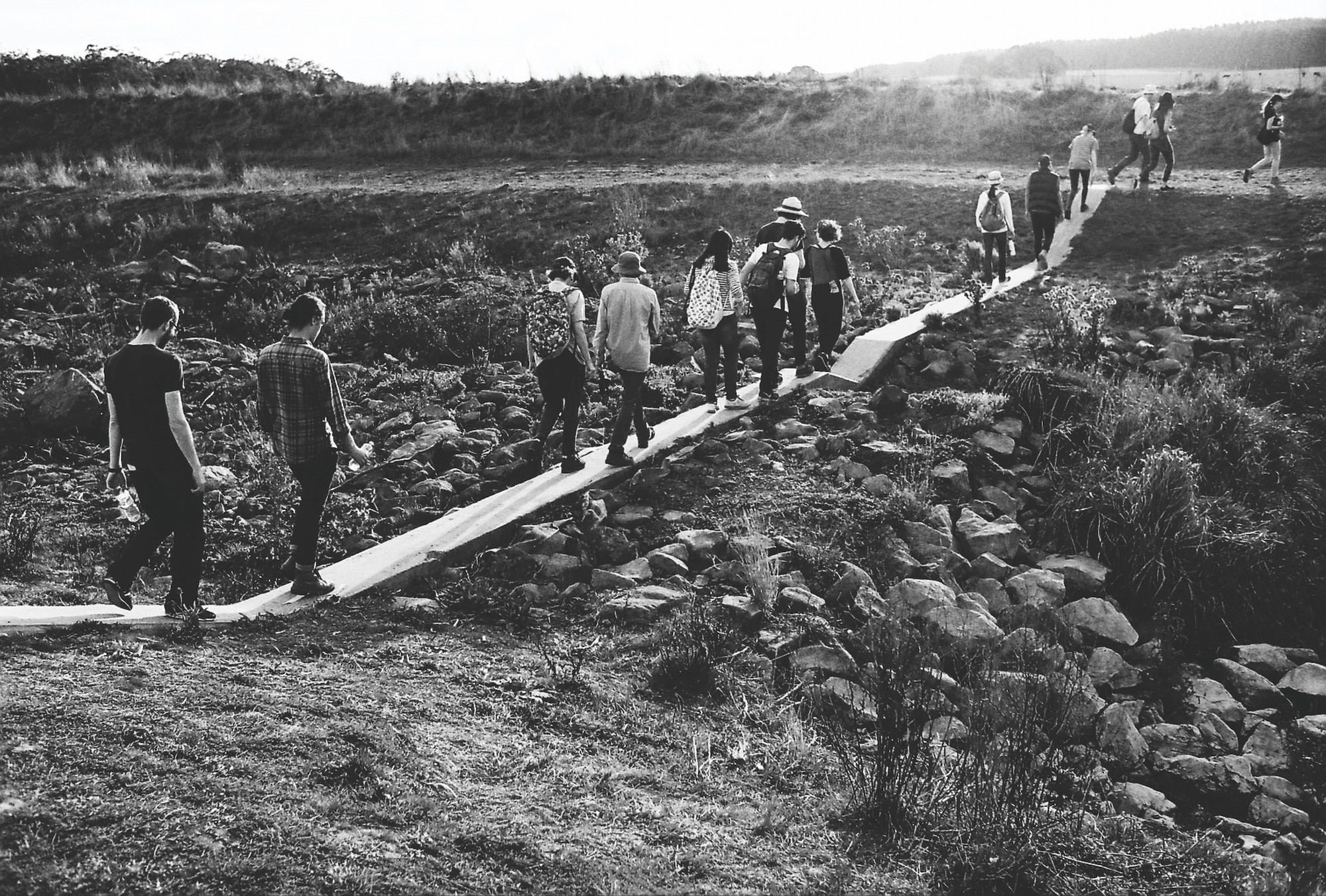

Research into the after-effects of modernity leads us to visit examples of ‘post-industrial hybrids’ – cumulative landscapes that absorb past actions as they are modified and adapted to dynamic conditions. The deep-time processes of the Gunditjmara people of Tae Rak (Lake Condah) in south-west Victoria show how careful interventions enable stewardship, repair, and rehabilitation of water systems.

For thousands of years, these Traditional Owners rearranged volcanic rocks that covered the low-lying plains below Budj Bim (Mt Eccles) to create a series of linked ponds that formed an eel-trap system. This is an example of a modified and augmented natural water landscape, generating cultural trade and allowing sustained human occupation. Construction of a small concrete weir across the remnant drainage channel allows Tae Rak to fill part way towards its natural level and makes a crossing, as seen in this photo; negotiations with adjacent landowners may progress to raise this level to its maximum floodable extent. The return of semi-permanent water brings back insects and birdlife, and with that comes a range of wetland plants re-establishing themselves in the previously drained farmland.

AUTHORS:

Nigel Bertram

Catherine Murphy

CONTRIBUTORS

N’arwee’t Carolyn Briggs

Daniel Kotsimbos

Rutger Pasman

Ben Waters

IMAGE

Monash architecture students

traversing the new concrete weir

(design by GHD) damming the outlet

drain at Lake Condah. Photograph by

Piers Morgan, 2016.